拉斐尔作品《粉红圣母》超高清大图

原图尺寸:6718×8348像素(760 DPI)超高清图

下载原图消耗6艺点

文件大小:112.47 MB

下载格式: ZIP ( PNG+JPG )

作品名称:粉红圣母

Madonna of the Pinks

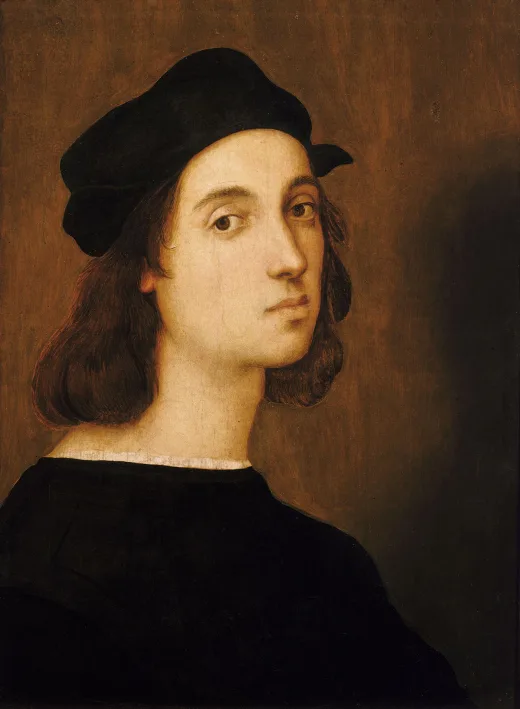

作品作者:拉斐尔(Raphael)

创作时间:约 1506–1507 年

作品风格:文艺复兴盛期

原作尺寸:27.9 × 22.4 厘米

作品材质:紫杉木板油画

收藏位置:伦敦国家美术馆

作品简介

《粉红圣母》(约1506-1507年,意大利语:La Madonna dei garofani)是一幅早期宗教画作,通常被认为是意大利文艺复兴大师拉斐尔的作品。这幅油画绘制在剧毒紫杉木板上(这是拉斐尔首次使用该材质),现藏于伦敦国家美术馆。

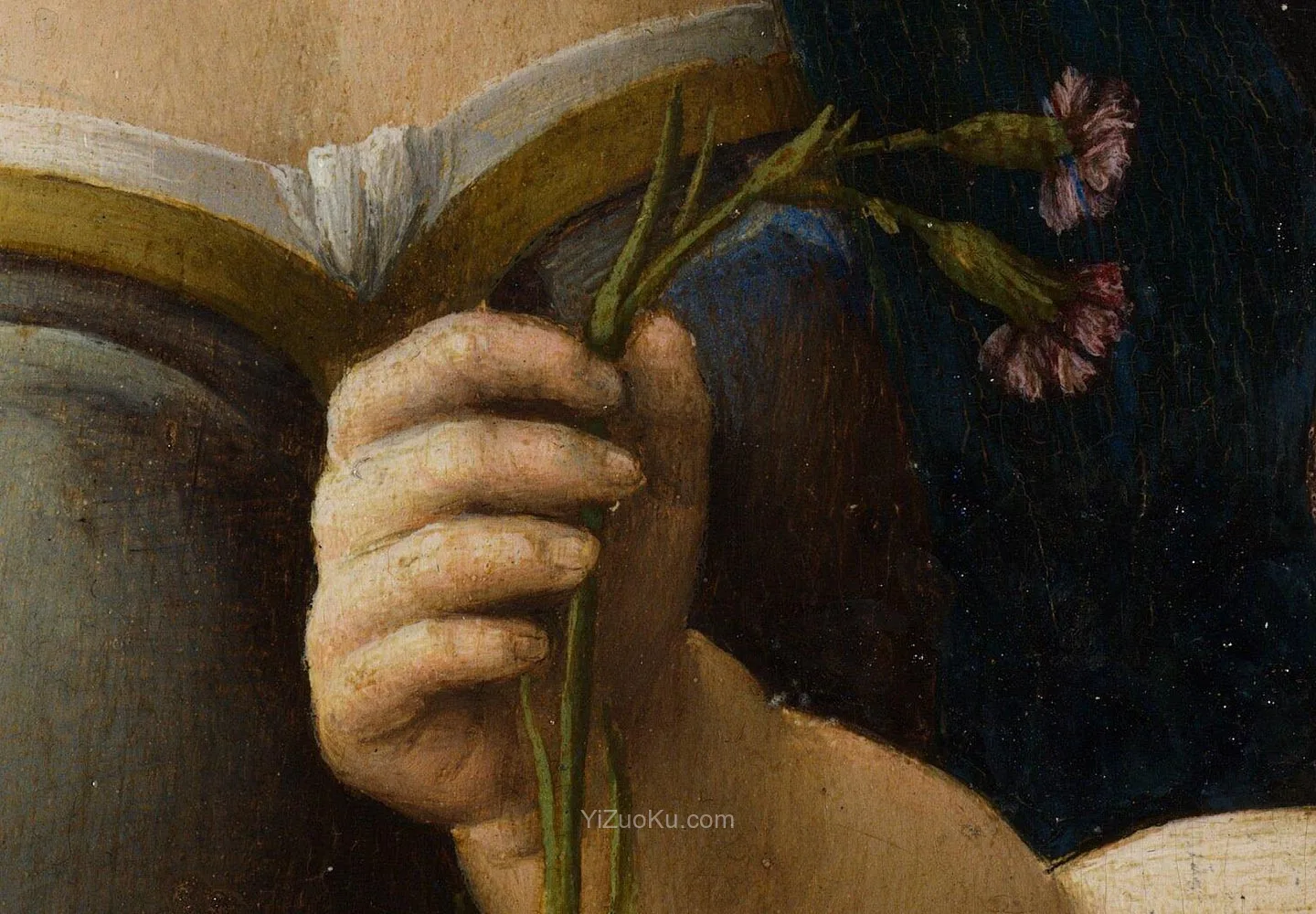

在这幅画中,拉斐尔将传统的圣母圣婴主题赋予了全新诠释。人物不再像早期画家作品中那样僵硬刻板,而是展现出年轻母亲与孩子之间应有的温柔情感。这对母子坐在意大利文艺复兴宫殿的卧室里,互赠康乃馨——这种花象征着神圣之爱和基督受难(他的折磨与钉十字架)。

这幅小画可能是为手持祈祷和冥想而作。一份16世纪20年代初的手稿清单表明,它是为"佩鲁贾修女马达莱娜·德利·奥迪"而作。

该作品自由借鉴了达芬奇的《柏诺瓦圣母》(现藏圣彼得堡冬宫博物馆)。一个多世纪以来,它一直被认为是复制品,但在1991年被重新发现为拉斐尔的原作。

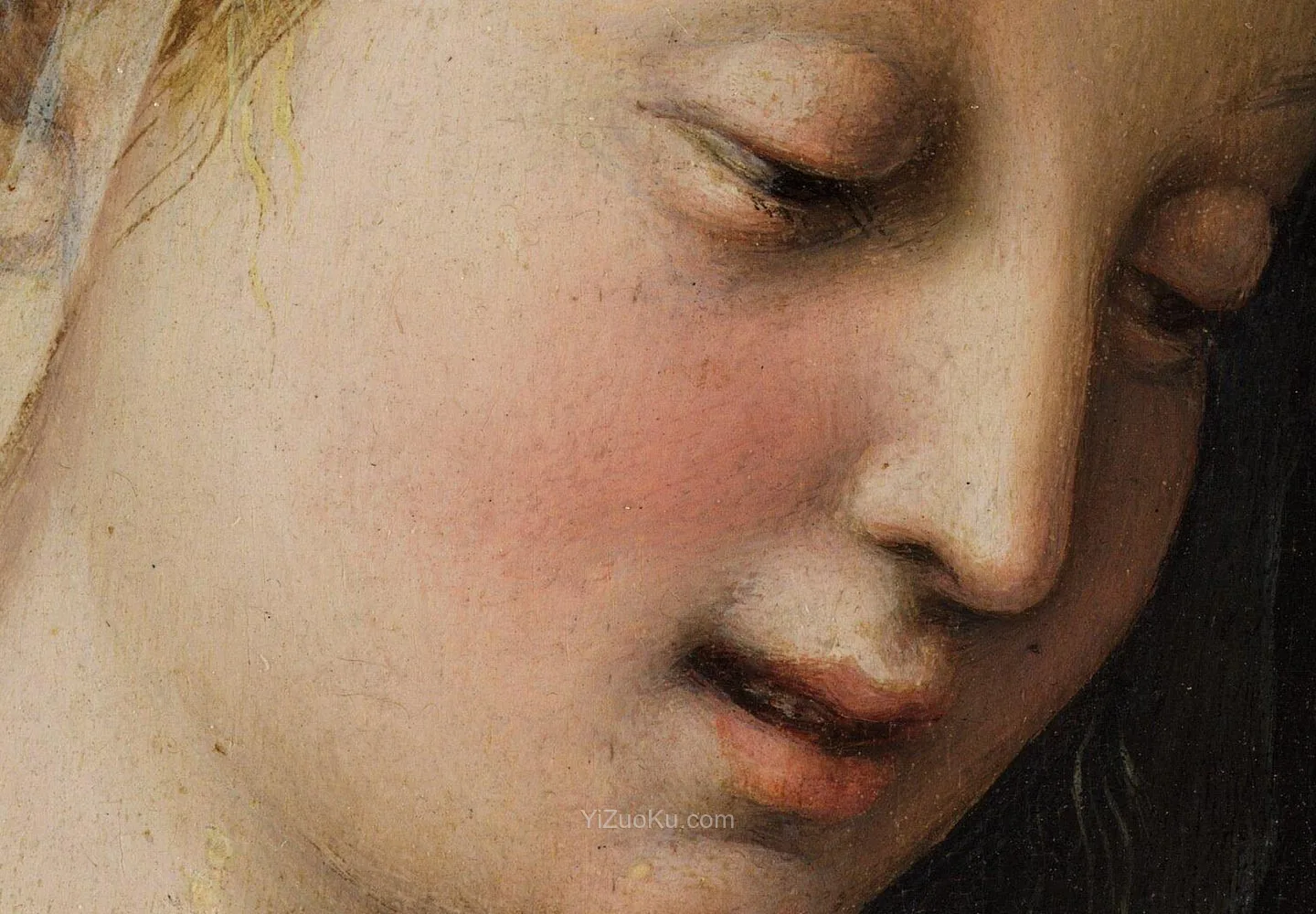

场景设置在意大利文艺复兴宫殿中圣母玛利亚的卧室。她坐在床尾的长凳或箱子上(绿色床帷在她身后打结),欣喜地看着膝上白色软枕上的圣婴。圣母和圣婴明亮的苍白肤色与阴凉的深色室内墙壁形成鲜明对比。透过拱形窗户可以看到阳光照耀下的景色,防御工事废墟依附在多岩石的山丘上。灰色石窗台有一个小缺口。

基督凝视着母亲递来的精致花朵——粉红色康乃馨(画作因此得名)。这种希腊语称为"石竹"的花朵是神圣之爱的传统象征,据传生长于圣母在基督受难时眼泪滴落之地。在世俗肖像中,石竹象征友谊和订婚,这也适用于此处,因为圣母被尊为基督的母亲和新娘。这一理念源自《旧约·雅歌》中神圣新郎与天上新娘的结合——这里的绿色床帷让人想起圣经文本中的绿色婚床。

人物光线并非来自窗户,而是左上角的人工光源。肌肤和衣物上微妙的光影处理显示出拉斐尔对尼德兰绘画的熟悉。打结的床帷、窗台上的逼真缺口以及圣母新月形的低垂眼睛也都反映出北欧绘画的影响。但主要影响来自达芬奇的《柏诺瓦圣母》,拉斐尔的构图与之非常相似。这种高度对应表明拉斐尔可能直接研究过这幅早30年的作品。冷色调、巧妙的光线、生动的人物互动和衣饰布置都反映出达芬奇的影响。拉斐尔通过和谐的用色将室内外的天国与尘世联系起来。他为圣母衣物选择的蓝灰色和黄色(而非传统的红蓝)也可能与达芬奇在《柏诺瓦圣母》中同样非传统的用色有关。

这幅保存完好的画作尺寸略大于时祷书(个人祈祷书),具有手抄本插画的精致,可能是为手持祈祷而作。16世纪20年代初的手稿清单表明它是为"佩鲁贾修女马达莱娜·德利·奥迪"而作。16世纪艺术传记作家瓦萨里曾提到马达莱娜是拉斐尔《圣母加冕》(约1503-4年为佩鲁贾圣方济各教堂奥迪礼拜堂绘制,现藏梵蒂冈绘画馆)的赞助人。国家美术馆这幅描绘贞洁圣母通过神圣花朵与圣婴交换神圣之爱的温柔画作,对一位通过宗教誓言与基督结合的贞洁寡妇而言,是合适的祈祷引导。

根据风格可追溯至1506-7年,很可能与拉斐尔为巴廖尼家族设计《基督下葬》祭坛画同期创作。巴廖尼家族在圣方济各教堂的礼拜堂正对着藏有拉斐尔《圣母加冕》的奥迪家族礼拜堂。

这幅画在16-17世纪广受赞誉,有许多早期复制品和版画。尽管阿尔尼克城堡的前任主人认为它出自拉斐尔之手,但学者们的质疑使其声誉受损,一度被认为只是艺术家失传作品的复制品。然而,2008-2015年担任国家美术馆馆长的尼古拉斯·彭尼博士在1991年重新发现了《粉红圣母》,他对拉斐尔的归属认定通过底稿和颜料的科学检测得到验证——这些都与拉斐尔去罗马前的作品特征相符。

红外反射成像技术(20世纪末的科学方法,早期复制者无法预见)揭示了异常自由和创造性的底稿——艺术家开始绘画前所作的草图。《粉红圣母》的底稿具有拉斐尔风格的典型特征:用宽弧线勾勒主要形态,小弧线表示指关节,影线表示阴影区域,钩状标记表示衣褶。显微镜检测显示底稿用金属笔绘制(拉斐尔常用这种媒介)。

底稿显示拉斐尔多次修改构图,特别是彻底重新设计了服装。他在绘画过程中遵循底稿主要轮廓但做了多处调整。一个重要改动是将原本紫色的床帷改为绿色。这类创作过程中的修改(公认创作过程的一部分)不会出现在复制品中,因为复制者面对的是最终版本。

通过显微镜检测也确认了颜料成分,这些颜料全部符合16世纪初拉斐尔在佛罗伦萨和翁布里亚工作时的特征。后来的复制者无法获得他使用的许多颜料,不得不使用文艺复兴时期意大利未知的后世颜料。最重要的是,画中含有一种极不寻常的闪亮深灰色颜料,最近被确认为金属铋粉末,也存在于拉斐尔其他作品中。据目前所知,铋作为颜料的使用仅限于16世纪早期的意大利中部绘画。

所有这些特征和证据表明,《粉红圣母》不可能出自拉斐尔同时代或其他时期的艺术家之手。

The Madonna of the Pinks (c. 1506 – 1507, Italian: La Madonna dei garofani) is an early devotional painting usually attributed to Italian Renaissance master Raphael. It is painted in oils on highly toxic yew wood, a first for a Raphael, and now hangs in the National Gallery, London.

In this painting, Raphael transforms the familiar subject of the Virgin and Child into something entirely new. The figures are no longer posed stiffly and formally as in paintings by earlier artists, but display all the tender emotions one might expect between a young mother and her child. The pair are seated in a bedchamber in an Italian Renaissance palace, and exchange carnations, which are symbolic of divine love and of Christ’s Passion (his torture and crucifixion).

This small picture may have been intended to be held in the hand for prayer and contemplation. A manuscript inventory dating to the early 1520s states that it was made for ‘Maddalena degli Oddi, a nun in Perugia'.

It is freely based on Leonardo da Vinci’s Benois Madonna (State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg). For more than a century it was believed to be a copy, but it was rediscovered in 1991 as an original painting by Raphael.

The scene takes places in the young Virgin Mary’s bedchamber in an Italian Renaissance palace. She sits on a bench or box at the end of her bed (the green bed curtain is knotted up behind her) and is shown delighting in her infant son, who sits on a soft white pillow on her lap. The brightly lit pale complexions of the Virgin and Christ Child stand out against the cool dark interior wall. Through the arched window is a sunny view with fortified ruins clinging to a rocky hill. There is a tiny chip in the grey stone window ledge.

Christ gazes at the delicate flowers offered by his mother – the pinks or carnations after which the painting is named. Known in Greek as dianthus, the flower was a traditional symbol of divine love and was reputed to have sprung from the earth where the Virgin’s tears fell during Christ’s Passion. In secular portraits the dianthus symbolised friendship and often betrothal, which would also be appropriate here, as the Virgin was venerated as both the mother and bride of Christ. This idea derived from the Old Testament Song of Solomon, in which the divine bridegroom is united with his heavenly bride – the green bed here recalls the green wedding bed of the biblical text.

The figures are not lit with light from the window but from an artificial light source at the upper left. The subtle description of light and shadow on the flesh and draperies reveals Raphael’s familiarity with Netherlandish painting. The knotted bed curtain, the view through the window with the illusionistic chip in the sill and the Virgin’s downcast, crescent-shaped eyes also reflect Northern European examples. However, the chief influence here is Leonardo da Vinci’s Benois Madonna (State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg), on which Raphael’s composition is closely based. The correspondence is so close as to suggest that Raphael was able to study Leonardo’s picture at first hand, though it was painted some 30 years earlier. The cool colours, artful lighting, lively interaction of the figures and arrangement of the draperies all reflect Leonardo’s work. Raphael has linked the heavenly and earthly worlds of the interior and exterior through his harmonious use of colour. His choice of blue-grey and yellow for the Virgin’s clothes (rather than the traditional red and blue) may also relate to Leonardo’s similarly unorthodox choice of colours in the Benois Madonna.

The painting, which is in excellent condition, is not much bigger than a Book of Hours (a personal prayer book), with the refinement of a manuscript illumination, and may have been intended to be held in the hand for prayer and contemplation. A manuscript inventory dating to the early 1520s states that it was made for ‘Maddalena degli Oddi, a nun in Perugia’. Maddalena was named by the sixteenth-century art biographer Vasari as the patron of Raphael’s Coronation of the Virgin, painted for the Oddi Chapel in S. Francesco al Prato, Perugia, in about 1503–4, and now in the Vatican Pinacoteca. The National Gallery’s tender painting, with its imagery of the chaste Virgin, betrothed by the exchange of divine flowers with divine love in the form of her baby son, would be an appropriate prompt to prayer for a virtuous widow who had herself espoused Christ by taking religious vows.

The painting can be dated on stylistic grounds to around 1506–7 and could very well have been produced at the same time that Raphael was designing and delivering the Entombment altarpiece for the Baglioni family, whose chapel in S. Francesco al Prato is opposite that of the Oddi family which housed Raphael’s Coronation.

The painting was well known and celebrated during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and many early copies and prints were made after it. Although believed by its previous owners at Alnwick Castle to be by Raphael, its reputation was eroded by the doubts of scholars until it was considered to be only a copy of a lost work by the artist. However, Dr Nicholas Penny, Director of the National Gallery from 2008 to 2015, rediscovered The Madonna of the Pinks in 1991 and his attribution to Raphael was verified by scientific investigation of the underdrawing and the pigments, which are both typical of Raphael’s work before he went to Rome.

The presence of exceptionally free and creative underdrawing – the drawing made by the artist before they began to paint – was revealed by infrared reflectography, a late twentieth-century scientific technique that no earlier copyist could anticipate. Much of the underdrawing in The Madonna of the Pinks is typical of Raphael’s style. It includes features familiar from many drawings, cartoons and other underdrawings by him: for example, broad arcs to lay in the principal forms, smaller arcs indicating the knuckles of the hands, hatching to denote areas of shadow and hook-ended marks to indicate drapery folds. Microscopic investigation shows that the underdrawing was carried out in metalpoint, a medium Raphael frequently used.

The underdrawing shows that Raphael changed his mind about the composition several times. In particular, he radically rethought the costume. He then followed the principal outlines of the underdrawing but made several changes and revisions during the course of painting. A major change was the bed curtain, which was originally coloured purple. These types of changes – a well-recognised part of the creative process – would not be present in a copy because a copyist would be working from the final version.

The pigments in the paints have also been identified using microscopic investigation. They are all characteristic of paintings made in Florence and Umbria in the first years of the sixteenth century, when Raphael was working there. Later copyists would not have been able to obtain many of the pigments he used, and would have had to employ later pigments, unknown in Renaissance Italy. Most importantly, the picture contains a highly unusual dark grey pigment with a shiny, sparkling appearance, identified recently as powdered metallic bismuth, which is present in other works by Raphael. The use of bismuth as a pigment is confined, so far as is known, to early sixteenth-century central Italian painting.

All these features and evidence mean that The Madonna of the Pinks cannot be attributed to another artist of Raphael’s time, or one at a later date.

局部细节