拉斐尔油画作品《亚历山大的圣凯瑟琳》超高清大图

原图尺寸:13157×17216像素(600 DPI)超高清图

下载原图消耗9艺点

文件大小:388.66 MB

下载格式: ZIP ( PNG+ JPG )

作品名称:亚历山大的圣凯瑟琳

Saint Catherine of Alexandria

作品作者:拉斐尔(Raphael)

创作时间:约1507–1509 年

作品风格:文艺复兴盛期

原作尺寸:72.2 × 55.7 厘米

作品材质:木板油画

收藏位置:伦敦国家美术馆

作品简介

《亚历山大的圣凯瑟琳》是意大利文艺复兴时期艺术家拉斐尔的一幅画作。画中,亚历山大的圣凯瑟琳神情狂喜地仰望着上方,倚靠在一个轮子上,这个轮子暗指她殉道时所用的刑具——磔轮(或称凯瑟琳轮)。

这幅画大约创作于1507年至1509年间,正值拉斐尔在佛罗伦萨逗留的末期,展现了这位年轻艺术家在过渡阶段的创作风貌。画中对宗教激情的描绘仍带有彼得罗·佩鲁吉诺(Pietro Perugino)的影子,但圣凯瑟琳优雅的体态——侧身扭转的姿势,则典型地体现了列奥纳多·达·芬奇对拉斐尔的影响,人们认为这是对达·芬奇失传画作《丽达与天鹅》的一种呼应。

1507 年拉斐尔为《亚历山大的圣凯瑟琳》创作素描稿

亚历山大的圣凯瑟琳是四世纪的一位公主,她皈依了基督教,并在幻象中与基督缔结了神秘的婚姻。当她拒绝放弃信仰时,皇帝马克森提乌斯下令将她绑在带刺的轮子上折磨至死。然而,一道闪电在轮子伤害她之前将其摧毁。随后,圣凯瑟琳被斩首。

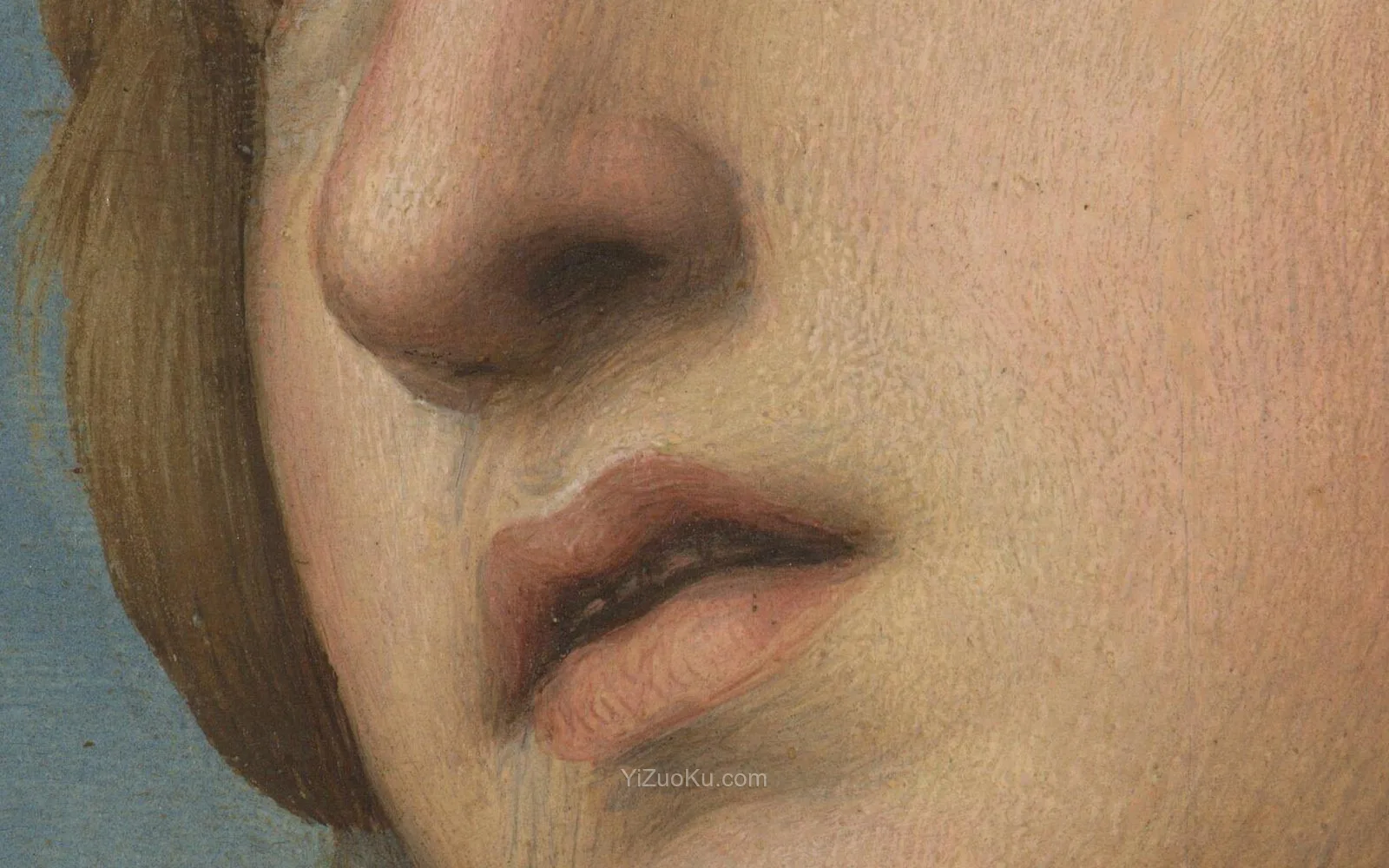

拉斐尔聚焦于这位圣徒信仰中的神秘面向,捕捉到了她手抚心口、嘴唇微张、在神圣的狂喜中仰望云端金色光芒的瞬间。画面前景是一朵蒲公英的种子头。在尼德兰和德国的绘画中,蒲公英常作为基督教哀悼和受难(基督的折磨与钉十字架)的象征出现。

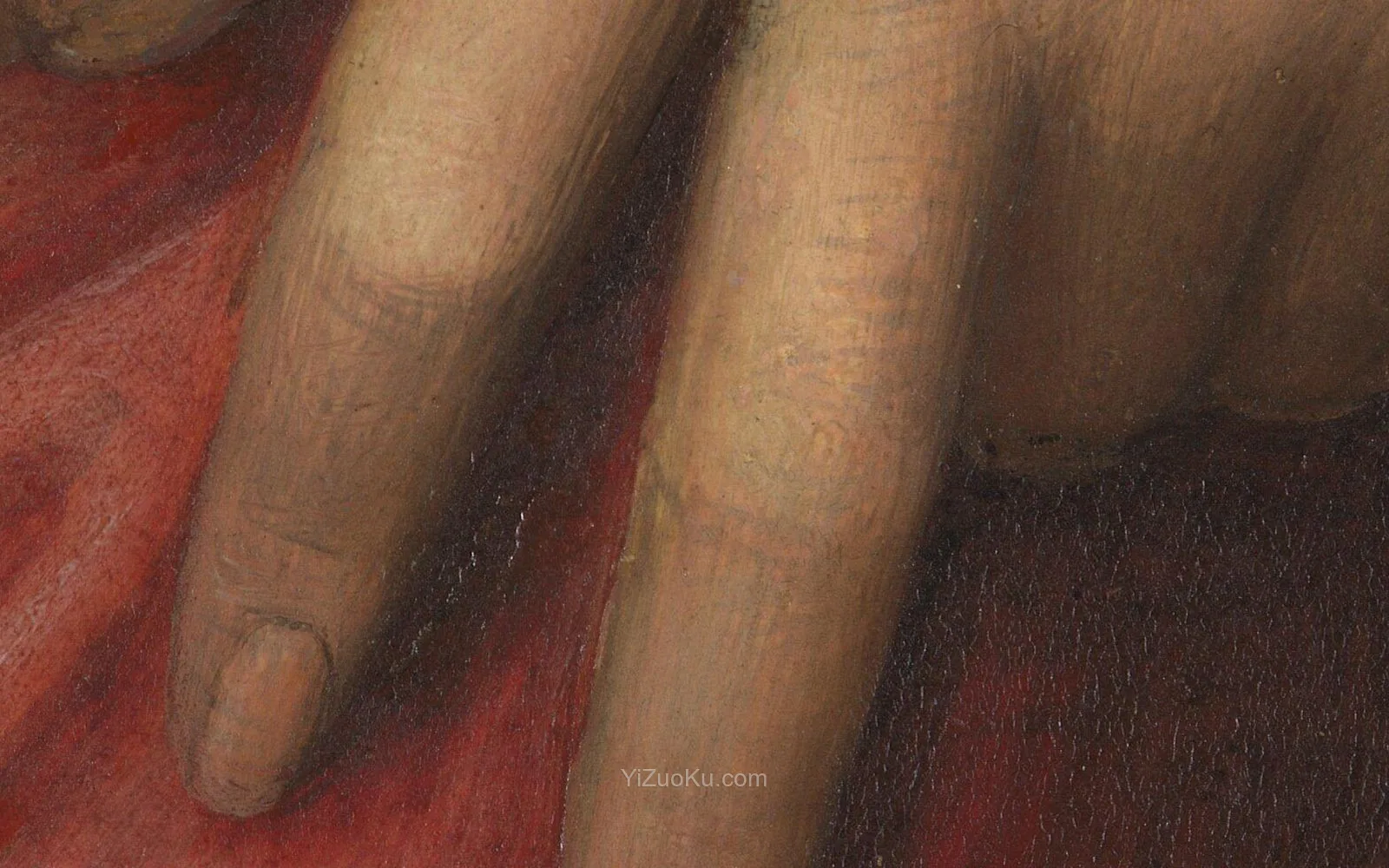

圣徒扭转的姿势反映了拉斐尔对佩鲁吉诺画作中蜿蜒优雅姿态的研究、对达·芬奇动态构图的借鉴,以及对米开朗基罗人物雕塑感的吸收。

在这幅画中,她被描绘在宁静的乡村风光中,倚靠在带刺的轮子上,但没有了通常作为殉道者象征的棕榈叶和剑。拉斐尔转而聚焦于她信仰中的神秘面向,捕捉到了她手抚心口、嘴唇微张、在神圣的狂喜中仰望云端金色光芒的瞬间。

在前景中,拉斐尔在岩石间描绘了几株纤细的植物,包括一朵蒲公英的种子头。蒲公英是一种苦味的草药,出现在描绘基督受难的尼德兰和德国画作中,象征着基督教的哀悼,特别是基督的受难。拉斐尔还在他稍早的《圣家族与棕榈树》(爱丁堡苏格兰国家美术馆)和1507年的《巴廖尼基督下葬》(佩鲁贾圣弗朗切斯科阿尔普拉托教堂)中加入了蒲公英的意象。

拉斐尔对处于狂喜状态的圣徒的大胆呈现,源自于此前为多联画屏(多面板祭坛画)中单一圣徒形象所采用的传统。拉斐尔可能与佩鲁吉诺共事过,后者的宗教人物——常常仰头抬眼——因其天使般的气质而受到同时代人的赞誉。佩鲁吉诺也将人物置于遥远的风景之中,并加入花卉的静物细节。然而,圣凯瑟琳的姿势比佩鲁吉诺作品中的任何形象都要动态得多,这揭示了达·芬奇和米开朗基罗对人物塑造方法的影响。

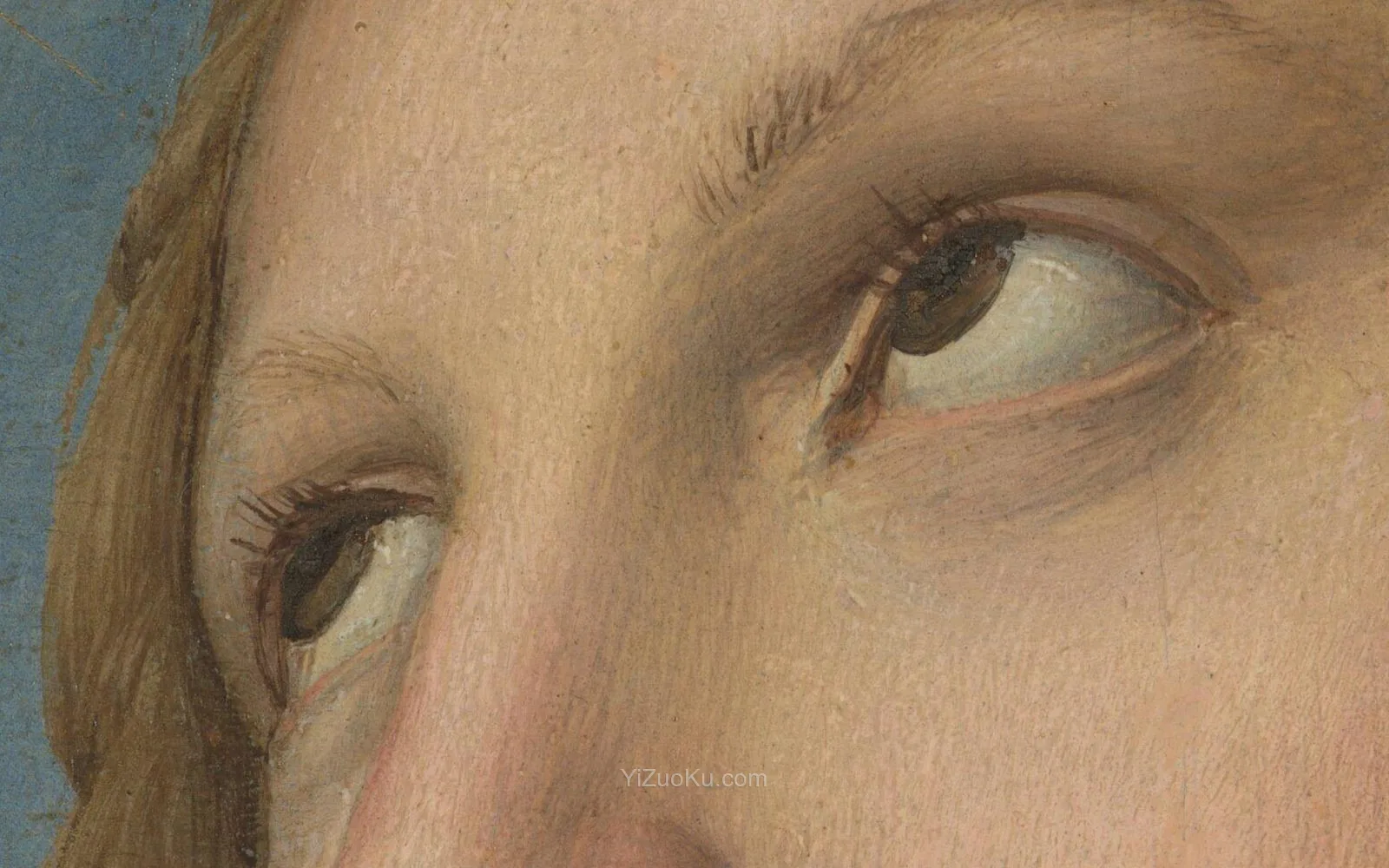

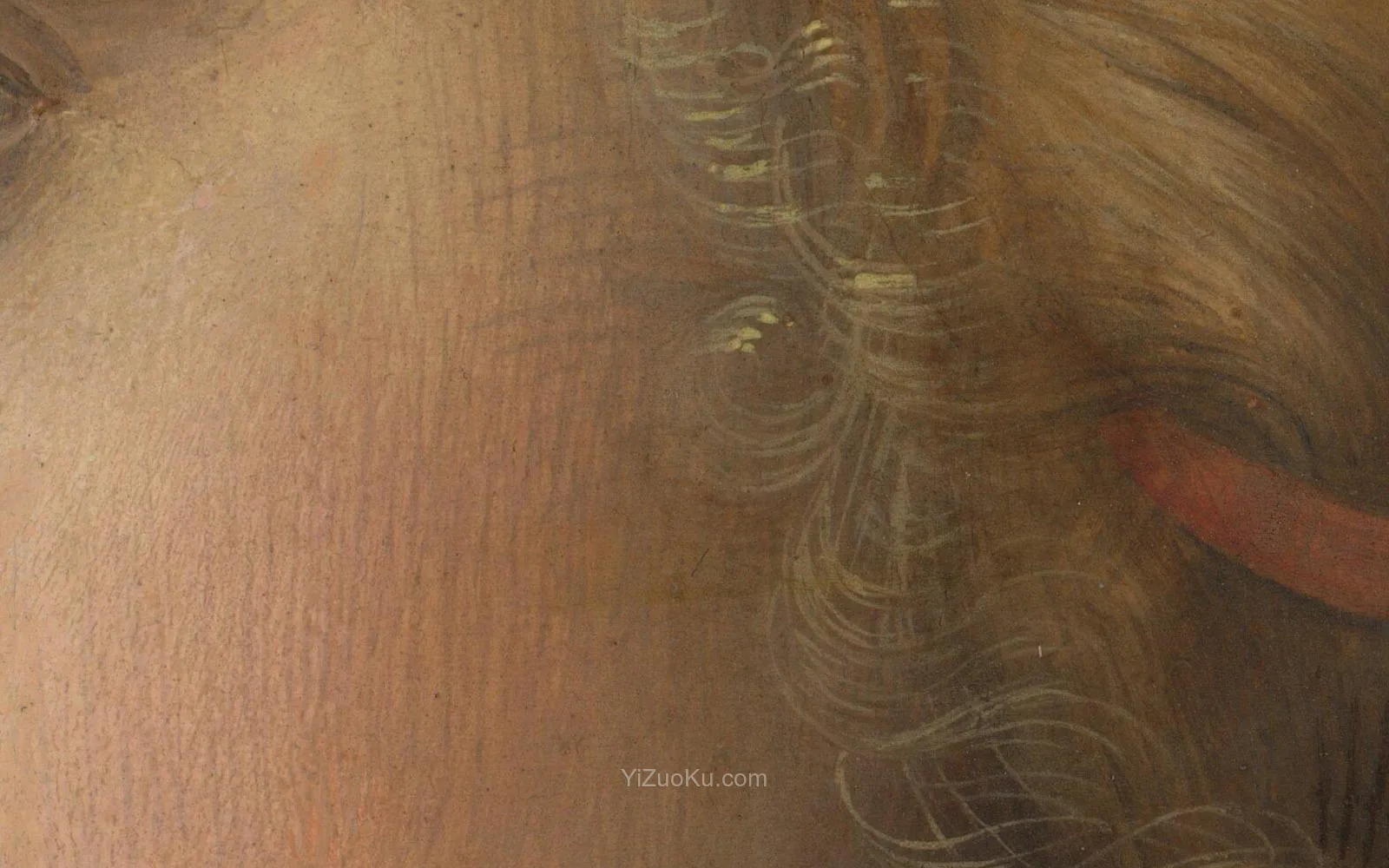

圣凯瑟琳优美弯曲的侧身扭转姿势——让人联想到维纳斯的古典雕像(也在波提切利的《维纳斯的诞生》中可见,现藏于佛罗伦萨乌菲兹美术馆)——部分源自达·芬奇的《丽达》(现藏于伦敦皇家收藏馆),拉斐尔在绘制《亚历山大的圣凯瑟琳》前不久曾临摹过这幅作品。她头发的螺旋状排列和斗篷的黄色衬里也是达·芬奇风格的典型特征。

雕塑般的庄重感和圣凯瑟琳抬起头的透视缩短效果,几乎可以肯定源自米开朗基罗为佛罗伦萨大教堂内部(现藏于佛罗伦萨美术学院)创作的未完成大理石雕像《圣马太》(1505-6年)。拉斐尔在他的《巴廖尼基督下葬》中为抬尸者绘制了这幅雕像的草图。拉斐尔笔下的圣凯瑟琳形象实际上是这两种灵感来源——达·芬奇的《丽达》和米开朗基罗的《圣马太》——的融合,但却极具个人特色,反映了他作品中普遍和谐这一根本理想。

目前尚不清楚是谁委托拉斐尔绘制了这幅《亚历山大的圣凯瑟琳》——它可能是作为私人敬拜的画作,或许是为某位特别敬奉这位圣徒或以其命名的人所绘。这幅画大约创作于1507年,当时拉斐尔正在绘制《巴廖尼基督下葬》,因此它也可能有一位佩鲁贾或佛罗伦萨的赞助人。作家彼得罗·阿雷蒂诺曾考虑将他所拥有的一幅“画有乌尔比诺的拉斐尔所绘圣凯瑟琳形象”的画作赠予法国王后凯瑟琳·德·美第奇。然而,无法确定这是否就是阿雷蒂诺1550年所记录并拥有的那幅画作。

Saint Catherine of Alexandria is a painting by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael. In the painting, Catherine of Alexandria is looking upward in ecstasy and leaning on a wheel, an allusion to the breaking wheel (or Catherine wheel) of her martyrdom.

It was painted c. 1507–1509, towards the end of Raphael's sojourn in Florence, and shows the young artist in a transitional phase. The depiction of religious passion in the painting is still reminiscent of Pietro Perugino, but the graceful contrapposto of Catherine's pose is typical of the influence of Leonardo da Vinci on Raphael, and is believed to be an echo of Leonardo's lost painting Leda and the Swan.

Catherine of Alexandria, a fourth-century princess, was converted to Christianity and in a vision underwent a mystic marriage with Christ. When she would not give up her faith, Emperor Maxentius ordered that she be bound to a spiked wheel and tortured to death. However, a thunderbolt destroyed the wheel before it could harm her. Catherine was then beheaded.

Raphael has focused on the visionary aspect of the saint’s faith, capturing her with her hand on heart and her lips parted, in a moment of divine ecstasy looking heavenwards to a golden break in the clouds. In the foreground is a dandelion seed head. The dandelion often appears in Netherlandish and German paintings as a symbol of Christian grief and the Passion (Christ’s torture and crucifixion).

The saint’s twisting pose reflects Raphael’s study of the sinuous grace of Perugino’s paintings, the dynamic compositions of Leonardo and the monumentality of Michelangelo’s figures.

Catherine of Alexandria, a fourth-century princess, was converted to Christianity and in a vision underwent a mystic marriage with Christ. When she would not give up her faith, Emperor Maxentius ordered that she be bound to a spiked wheel and tortured to death. However, a thunderbolt destroyed the wheel before it could harm her. Catherine was then beheaded.

She is depicted here in a peaceful rural landscape leaning on the spiked wheel but without her usual attributes of a martyr’s palm and the sword. Raphael has focused instead on the visionary aspect of her faith, capturing her with her hand on heart and her lips parted, in a moment of divine ecstasy looking heavenwards to a golden break in the clouds.

In the foreground he has painted a few delicate plants among the rocks, including a dandelion seed head. The dandelion is a bitter herb that appears in Netherlandish and German paintings of the Crucifixion and was symbolic of Christian grief and in particular Christ’s Passion. Raphael also included a dandelion clock in his slightly earlier Holy Family with a Palm Tree (Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh) and his Baglioni Entombment of 1507 (S. Francesco al Prato, Perugia).

Raphael’s bold presentation of the saint in ecstasy developed out of conventions previously adopted for single figures of saints for polyptychs (multi-panelled altarpieces). Raphael probably worked alongside Perugino, whose religious figures – frequently with upturned heads and raised eyes – were praised by contemporaries for their angelic air. Perugino also placed his figures against distant landscapes and included still-life details of flowers. However, Saint Catherine’s pose is far more dynamic than anything found in Perugino’s works, revealing the influence of Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s approaches to the figure.

Saint Catherine’s beautiful curving contrapposto pose – reminiscent of a classical statue of Venus (and also seen in Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, Uffizi, Florence) – is partly derived from Leonardo’s Leda (Royal Collection, London), which Raphael had copied not long before painting his Saint Catherine. The spiralling arrangement of her hair and the yellow lining of her mantle are also characteristic of Leonardo’s approach.

The sense of sculptural monumentality and the foreshortening of Saint Catherine’s raised head almost certainly derive from Michelangelo’s unfinished marble Saint Matthew (1505–6) for the interior of Florence Cathedral (now Accademia, Florence). Raphael made a drawing of it for the bearers in his Baglioni Entombment. Raphael’s figure of Saint Catherine is really a fusion of these two sources – Leonardo’s Leda and Michelangelo’s Saint Matthew – but made very much his own, and reflecting the ideal of universal harmony that was so fundamental to his works.

It is not known who commissioned Raphael’s Saint Catherine – it may have been intended as a picture for private devotion, perhaps for someone particularly devoted to the saint or named after her. Painted in about 1507 when Raphael was working on the Baglioni Entombment, this picture may also have had a Perugian or Florentine patron. The writer Pietro Aretino considered presenting a picture in his possession ‘in which is the image of the figure of Saint Catherine, by Raphael of Urbino’ to Catherine de' Medici, Queen of France. However, it is impossible to tell whether this is the painting once owned by Aretino and recorded in his possession in 1550.

局部细节